Homo ludens or the birth of the Musement.

Bataillean Heterological Approach to the Anthropological View of Play’s function in Human Evolution

Bataillean Heterological Approach to the Anthropological View of Play’s function in Human Evolution

Six million years ago humans shared a common ancestor with chimpanzees. Chronically after that many hominids appeared as australopithecus ramidus 4.5 million years ago; homo habilis 2 million years ago with first stone tools and a increase in meat consumption; homo erectus 1.8 million years ago as African emigrants; homo neanderthalensis as survivors in Europe until 30,000 years ago, and finally, homo sapiens sapiens 100,000 years ago with the emergency of the human modern mind during the cultural explosion 60,000-30,000 years ago.

During the last 4 million years, the brain has increased its size. The first of the two great moments of brain’s evolution happened around 2 and 1.5 million years ago as homo habilis appeared. Walking on two feet didn't only provoke the use of the tool, but also increased communication possibilities. Freedom for the torso, capacity of the lungs and the diaphragm to produce complex sounds… approximately 1.6 million years ago, language emerged, and with it, first love’s declarations, sincere and not sincere.

Brain’s size increase continued and with it, our human survival capacities, from hunting to singing, dancing and painting. The second great evolutionary moment happened between 500,000 and 200,000 years ago. The oldest skeletons accompanied by tools come from North Africa (1 million years ago). Art objects and personal decorations come from 70,000 years. Agricultural knowledge comes from 10,000 years ago and first great civilizations arose 5,000 years ago.

All these archaeological data were helpful for the French writer Georges Bataille (1897-1962) to argue that eroticism, immortality and transcendence longings as well as ecstasy phenomena, in the temporary scale of human existence on the Earth (hundred of millions of years), are surprisingly new: only 150,000 years. Bataille was fascinated by many anthropological works and discoveries (Marcel Mauss, Roger Caillois), thinking that behind these exorbitant temporary numbers humans could understand more about their own nature. Cave paintings like those of Lascaux could reflect the beginnings of human nature.

Anatomically, modern humans well-known as homo sapiens appeared in South Africa and the Near East 100,000 years ago. It is thought that we evolved from an archaic sapiens, homo heidelbergensis who lived 400,000-100,000 years ago in Asia and Africa descending from homo erectus, 1.8 million years ago. Researchers suggest that homo neanderthalensis has also evolved from heidelbergensis, but his physical features differ from ours. During Upper Paleolithic age, this homo appeared with prominent jaw, semi-erect legs and hairy body, manufacturing tools of carved bone and burying their fellows. (100,000 years ago). Although the size of his brain was similar to ours (between 1200 and 1750 cm3), European glacial atmospheres determined his physical and mental capacities for an extremely demanding nomadic lifestyle.

Although neanderthal was homo faber, that is to say, a being whose principal activity consisted in manufacturing tools and working, his great mystery doesn't come from this condition. Even though homo neanderthalensis’ brain was similar in size to ours, he didn’t develop its capacities as us, neither art nor complex knowledge. Nevertheless, it should be recognized that the first sepulchers are those belonging to him (100,000 years ago). Briefly, neanderthal was closer to us than primates due to his own aesthetical consciousness of death. (3)

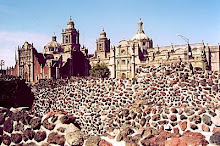

In this sense, Bataille argues that neanderthals have succumbed to sapiens’ violence. It has been said that competitive advantages of homo sapiens were related to his agile physiognomy. 100,000 years ago he began to disperse through the territories of Africa and East Asia, arriving to Australia 60,000 years ago and to Europe 30,000 years ago. Chauvet’s cave paintings and Great Goddess's beautiful figures known as "Venus" would appear 28,000-17,000 years ago, later Lascaux’s ones (17,000-15,000), and finally Altamira’s ones (12,000). (4)

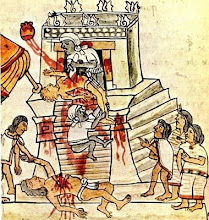

Rather than thinking about the evidence of neanderthal’s graves or the athletic physiognomy of sapiens, Bataille’s work invites us to understand art, eroticism and sacrality as primary human conditions. These three human features appeared during a great cognitive evolution.

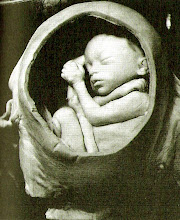

On September 12th 1940, French children discovered among the forest of Vézère in France (Montignac) an uterine hole covered by rocky sedimentations: Lascaux, a grotto adorned during Paleolithic times in whose depths remained animal’s paintings as well as one of the first anthropomorphical representations in a natural cavity of very difficult access, the Well (Puits) a disconcerting enigma: a bird-headed man, with an erected penis, buried in front of a bison that dies. A bird above the man and a rhinoceros that goes away… According to Bataille, cave paintings as L’homme du Puits show us the relationship between aesthetics, eroticism and sacrality. From other point of view, a cognitive archeologist from the University of Reading, Steven Mithen, suggests that cave paintings demonstrate the greatest step of cognitive evolution: the connection between different aspects of human intelligence. In other words, he sustains the hypothesis that those paintings constitute the archeological testimony of cognitive fluidity. Contemporary evolutionary psychology of Leda Cosmides, John Tooby, Michael Jochim, Thomas Wynn and Jerry Fodor as well have outlined that human mind consists in different cognitive modules; each one specialized in a specific type of intelligence, for example, modules to model animal behavior, language skills, manufacturing tools or social interaction. All this reminds us the dramatic transformations in the human behavior that happened during the cultural explosion of our species 60,000-30,000 years ago: Art, Religion and Technology, as well as Bataille had done it a half century ago through another way of reflection: heterological thought.

Suggested lectures

Bataille, Georges. “La volonté de l’impossible.” Dans Oeuvres complètes. Paris, Gallimard, NRF, p. 19. T. XI.

Taylor, Timothy. The Prehistory of Sex. Four Million Years of Human Sexual Culture. New York, Bantam Books, 1997. p. 3.

Bataille, Georges. Lascaux ou la naissance de l’art. Genève (Suisse), Éditions d’Art Albert Skira, 1955:

Michael Chapman’s film, The Clan of the Cave Bear (1983) reconstructes the encounter between Neanderthals and Sapiens based on Jean M. Auel’s novel.

Mithen, Steven. The Prehistory of the Mind. The Cognitive Origins of Art and Science. New York, Thames and Hudson, 1996. Evolutionay psychology has been also developed mainly at UCLA (Santa Bárbara) and particularly at St. Andrews’ University.

Suggested lectures

Bataille, Georges. “La volonté de l’impossible.” Dans Oeuvres complètes. Paris, Gallimard, NRF, p. 19. T. XI.

Taylor, Timothy. The Prehistory of Sex. Four Million Years of Human Sexual Culture. New York, Bantam Books, 1997. p. 3.

Bataille, Georges. Lascaux ou la naissance de l’art. Genève (Suisse), Éditions d’Art Albert Skira, 1955:

Michael Chapman’s film, The Clan of the Cave Bear (1983) reconstructes the encounter between Neanderthals and Sapiens based on Jean M. Auel’s novel.

Mithen, Steven. The Prehistory of the Mind. The Cognitive Origins of Art and Science. New York, Thames and Hudson, 1996. Evolutionay psychology has been also developed mainly at UCLA (Santa Bárbara) and particularly at St. Andrews’ University.